The Men Who Said No

Although many men from Leominster and the surrounding villages rushed to join up once War had been declared, there were others who believed the war was completely wrong. The Military Service Act of 1916, which introduced compulsory military service, contained a ‘conscience clause’ whereby men who objected could be freed from conscription.

During the 19th century, there was a strong Quaker community in Leominster. Since the foundation of Quakerism, a religious sect, in the 17th century, Quakers have had a strong tradition of pacifism – a belief that all war and violence is wrong.

Several young men in Leominster refused conscription. They were not all Quakers, but clearly had links with them, including belonging to the Leominster Adult School, a Quaker enterprise.

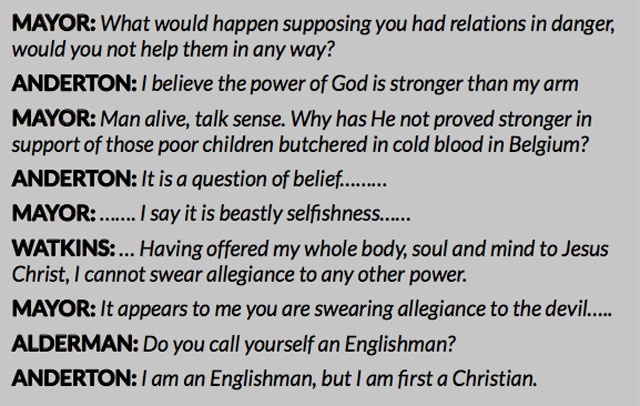

Those who claimed to be ‘conscientious objectors’ faced military tribunals where they had to argue their case. The tribunals were like magistrates courts, with local dignitaries, including the Mayor, sitting on them.

The ‘Leominster News’ in 1916 contained many reports of Local Tribunals that were held in the town. There were some strong exchanges between the two sides:

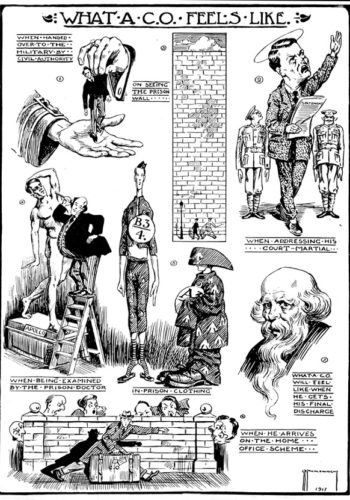

The War experiences of Leominster’s conscientious objectors were very different, depending on the choices they made.

William Anderton was rejected as a conscientious objector by the Local Tribunal. He was granted exemption by the County Tribunal, provided he joined the Royal Army Medical Corps. However, the RAMC refused him, and he was court martialled for disobeying orders in the Non Combatant Corps and sentenced to two years hard labour. He was sent to Wormwood Scrubs Prison, where he was finally classified as a Class A Objector by the Central Tribunal. The Brace Committee, which ran work centres around the country for the Home Office, sent him to mend roads in Suffolk. He ended the War years in Dartmoor Prison.

Aubrey Ross , who grew up at 12 Bridge Street, was a member of the Leominster Open Brethren, an evangelical Christian group. He joined the Royal Army Medical Corps as a stretcher bearer, and served at the Battle of the Somme. This was very dangerous work; often the stretchers could not be carried along the narrow twisting trenches, and so the unarmed bearers had to walk at ground level, exposed to enemy sniper fire.

Arthur Clery was charged with being absent without leave from the Army, and arrested at 2am, to appear before Leominster magistrates. He eventually joined the Quaker Friends Ambulance Unit, which allowed non-combatants to care for wounded soldiers, instead of fighting. He worked in two hospitals in Birmingham and York, caring for limbless soldiers, and on two hospital ships, which carried the wounded back from France across the submarine infested English Channel. It was dangerous work, and he was awarded a Red Cross medal for his service at the end of the War.

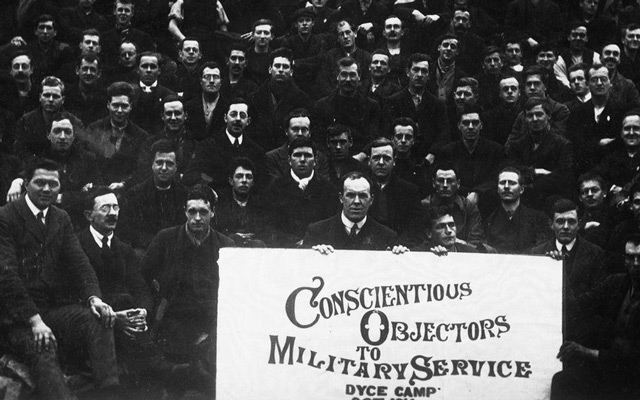

Henry Watkins was arrested at the same time as Clery, convicted of absenteeism and fined 40 shillings. His trial was postponed because of his weak heart. He later spent time in both Winson Green and Wormwood Scrubs prisons, before being sent to work at the Dyce stone quarry in Aberdeenshire. This was a desolate work camp in northern Scotland, where the COs were housed in Boer War tents, and made to break granite.