Crisis in Agriculture

The outbreak of War had a rapid effect on food prices in the town. On August 7th, the Mayor of Leominster wrote an appeal in the News, saying:

“The inhabitants of Leominster and District are urged NOT TO ASSIST IN RAISING FOOD TO PANIC PRICES by attempting to lay in stocks….. As Mayor, I appeal to patriotic citizens to keep cool and maintain their reputation as Englishmen.”

A week later, a letter was sent to the Mayor, saying that some cottagers had had to kill their pigs, as dealers had already doubled the cost of pig meal. His reply, published in the News, was emphatic:

“..Some people….have stooped to make themselves secure at the expense of the community as a whole by laying in heavy stocks of provisions……Such conduct is as bad as if they were to take up the sword on behalf of the enemy…”

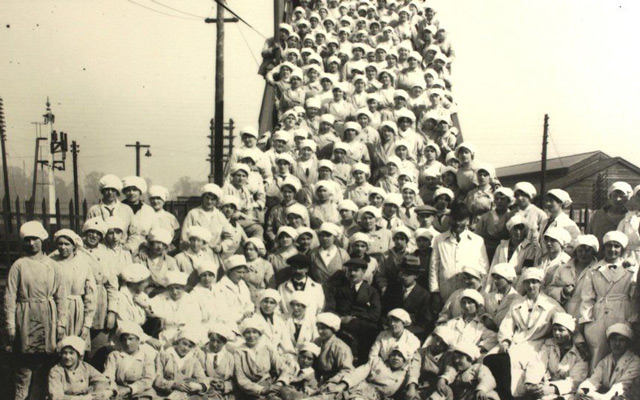

By the end of August central government set maximum food prices. Luckily, the harvest was good that year. The War brought changes in the agricultural labour market. As more men left farms for the Front, there were serious shortages of experienced workers all over the country, and by 1916, national output was down 15-25%. There was increasing fear that crops would be left to rot and food would have to be rationed. Following the formation of the Women’s Land Army in 1915 the Leominster Agricultural War Committee was set up, to discuss the problems. At first it was made up entirely of men, but in 1916 they co-opted two women onto the Committee, who recruited as many women to farm work as they could.

There was deep scepticism amongst the men about whether the new female workers would pull their weight. The Leominster News reported one alderman saying:

“…a lot of fresh women who had never worked on a farm…would not be of much value. They would want a wage which would be more than the work was worth.”

In June 1916, the News reported the experience of a farmer from Docklow. Having lost 5 out of 12 men to work his 500 acre farm, he employed two young women – a dress maker and a milliner from Bristol – who had never worked outdoors before. He said that they worked an 11 hour day, mucking out, driving the wagon, caring for animals, manuring, and scuffling. They were: ” …a huge success and their keenness and willingness had sharpened up every man on the farm.” He was “proud of his farm girls and anyone who doubts what they can do can come and see for themselves.”

The shortage of men also had an effect on the use of child labour. School log books regularly record high rates of absenteeism when there was work to be done. In addition, a number of parents who had boys close to the statutory school leaving age applied for permission for them to leave school early, as they already had paid jobs waiting for them on local farms.