At Home in the Town

The outbreak of War had an immediate effect in the town. Some Post Offices were open all night on August 4th, delivering telegrams to army reservists, ordering them to assemble. Motorists drove round delivering messages. On the 5th, soldiers left from Kington and Leominster to travel to Pembroke Docks, and crowds gathered to see them off. On the 6th, a long convoy of lorries passed through the town, on their way from Manchester to Avonmouth, having been commandeered from private companies by the government for military use.

Responses from townspeople to news of the War varied. Within days, the Leominster News asked inhabitants to report any German residents they knew of to the Police. False rumours began to spread about certain people who were perceived to have ‘foreign’ names – especially Mr Rouch, and Mr Hoff, who were both English. Mr Rouch, who ran a shop in South Street, was forced to take out advertisements in the Leominster News, and offer a £50 reward, to save his business from ruin. Even an English couple who had recently moved from St Petersburg came under suspicion.

There were isolated cases of vigilantism. One anonymous letter sent to the Leominster News complained that a cyclist had been threatened at night by a group of men and women brandishing a rifle, shouting “Friend or Foe?”.

More positively, when Belgian refugees, escaping from the German invasion of their country, began arriving in October 1914, they were kindly received. Accommodation was found, money raised, and school spaces secured for several children. Most stayed until 1919, and in recognition of the town’s hospitality, an organising committee member was awarded a medal by the King and Queen of the Belgians.

Everyone worked very hard to support the War effort, either by raising money, or in other ways. Between December 1914 and May 1919, 164,411 eggs were collected by the Leominster depot of the National Egg Collection for the Wounded, and sent to recovering soldiers.

Fundraising events were organised to buy warm clothes for the troops; school girls were set to knitting caps and socks for soldiers; turkeys and dolls were raffled at Christmas; and a bullock was sold for £737 in aid of the Red Cross by Tenbury farmers.

Different groups chose different causes to support. The Quaker community raised money for the Friends Ambulance Unit and refugees; village schools organised concerts and magic lantern shows while Scouts helped at the cottage hospital and with gardening and other jobs.

Children wrote letters to Old Boys fighting at the Front. These were genuinely appreciated, and many soldiers took the trouble to say thank you on prepaid cards.

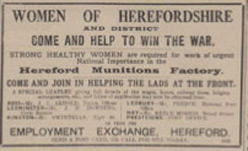

By September 11th 1914, the Leominster International Stores was already advertising for new female staff, having lost male employees to the Army. As the War continued, more and more women joined the paid workforce in shop, factory & farm.

In 1916, when the munitions factory opened at Rotherwas there was a shortage of accommodation for the thousands of female workers, and the Mayor organised a house to house survey to find householders who would accept women as lodgers in their spare rooms. Many were living independently of their families for the first time in their lives.

In many ways, those who were left in Leominster during the War years strove to keep life as ‘normal’ as possible. School life carried on as usual, even when teachers left for War service. Agricultural production was increased by the introduction of more mechanisation, female labour and the ploughing of marginal land. On occasions, the War intruded. In March 1916, there was an air raid warning in the town, and people were asked to extinguish their lights, which most regarded as a joke.

Throughout the War, and for some years afterwards there was a sad succession of funerals in the town, for those soldiers who had made it back to England before dying of their wounds.